Ettore Sottsass, the magical object

Italian born in Austria, architect, writer, designer, Ettore Sottsass opposed his work to rationalism and never ceased to lay claim to an emotional experience of objects. The Centre Pompidou keeps alive his ritual punctuation of a cosmic whole.

The exhibition brings together a unique collection of major historical pieces by Italian designer Ettore Sottsass Jr. (Innsbruck 1917 – Milan 2007), from the 1940s through to the 1980s. More than 400 works (drawings, paintings, design objects), 500 photographs and 200 original documents from the archives of the Kandinsky library underscore all the creative components of his work.

“I have always thought that design begins where rational processes end and magic begins” - Ettore Sottsass Jr.

Painting, sculpture, literature, modern avant-gardes and radical architecture are all displayed in the course of a chronological presentation.

The high point of the exhibition is the partial reconstitution of an historic exhibition in Stockholm in 1969, with the presentation of an exceptional collection of monumental ceramics, reflecting his approach to «magical design».

For Sottsass, there was no difference between a ceramic item, a piece of furniture, architecture, a photograph or a text, each being a ritual punctuation of a cosmic whole.

Ettore Sottsass Jr. was a precursor at every stage of his life. He envisaged design as a manner of reforging architecture, as well as weaving a new connection between human beings and objects

The Modern Avant-Garde

After a "happy childhood in the mountains", Ettore Sottsass trained in the 1930s with painter Luigi Spazzapan, who introduced him to modern art. He also studied architecture at the Politecnico in Turin, graduating in 1939. In the 1940s Ettore Sottsass's creative language was sustained by the artistic avant-gardes, from the Fauves to the Cubists, Wassily Kandinsky to Max Ernst, Jean Arp to Alexander Calder, through pictorial work on colours, motifs, rhythms and structures. Sottsass drew, painted and also made many sculptures, which have now disappeared.

In 1947, Ettore Sottsass began to make furniture objects and interior layout projects. In this respect, the Grassotti Cabinet (1948-1949, picture below) is an exceptional piece in the Centre Pompidou collection, a testament to the influence of the Neoplasticist De Stijl movement spearheaded by Theo van Doesburg in the 1920s-1930s, but also to purist painting and the architecture of Le Corbusier (Villa Savoye, 1933).

The architectonic forms of the cabinet resemble colour screens that spatialise the object. That same year, the Spatial model (1947, picture right), with its kinetic volumes, testified to the integration of movement and the fourth dimension of time in his sculpture, which was close to the Constructivism of Antoine Pevsner.

The Magical Object

Ettore Sottsass made his very first ceramics in 1956. Clay is a humble material that connects man with the cosmos, opening the way to a "ritual and symbolic function” of objects. In ceramics, the primitive, the totemic and the magical came together in an archaic time. Ceramics embodied a culture of anonymous objects, in resonance with his interest in anthropology, vernacular architecture and folk art.

In 1958, Ettore Sottsass was a consultant for Olivetti, where he formed a unique relationship with Adriano Olivetti. In 1959, he designed Elea, the first electronic computer, as well as typewriters for Olivetti.

Following a trip to India in 1961, he caught a serious illness that led him to California, where he remained in hospital, between life and death, for long months. Punctuated by diagrammatic drawings, Céramiques des ténèbres (Ceramics of Darkness) were born out of this sombre period in 1963. Thanks to Fernanda Pivano, his first wife, he developed friendships with the writers of the Beat Generation (Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, etc.).

In 1967, the exhibition entitled "Menhir, Ziggurat, Stupas, Hydrants and Gas Pumps" at the Sperone gallery in Milan presented ceramics on an anthropomorphic scale, influenced by Pop Art and marking the passage from the small scale of objects to that of the spatial environment. Imagined as early as 1962 while hospitalised in the United States, but designed between 1964 and 1965, this series of around twenty terracotta ceramics was made the following year by the Bitossi workshop in Montelupo in the region of Florence. These large totems, situated between eastern and western culture, evoke a magical and primitive dimension of objects. They consist of a stack of circular, striped or monochrome elements that punctuate their vertical ascension.

The "ritual weight" that Sottsass bestowed on objects can be found in all scales, including his creations of jewels. Veritable miniature architectures, they were inspired by ancient or ethnic finery and were intended, according to Sottsass, for "queens and vestal virgins more than for the women of our society".

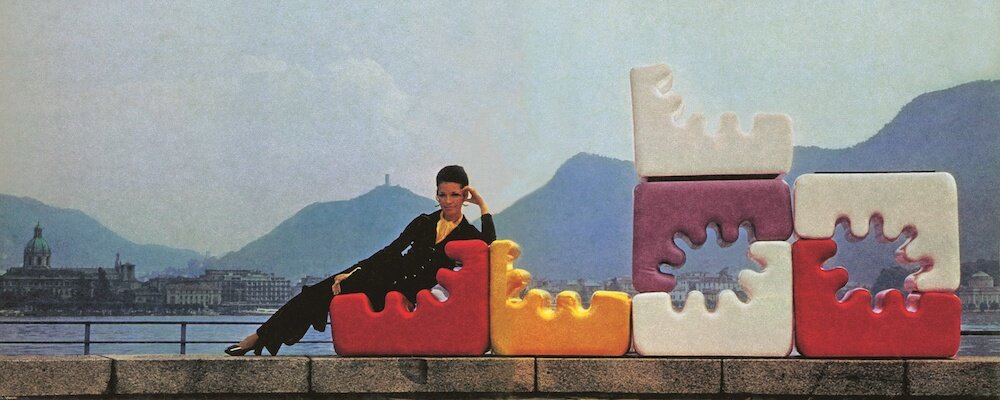

The years 1960-1970 were also a period of radical experimentation, between design and architecture, as evidenced by the Container Furniture made in 1972 for the MoMA in New York.

In the 1970s, Ettore Sottsass collaborated regularly with the Casabella review, directed by Alessandro Mendini. In 1968, he produced Pianeta fresco, a counter-culture magazine, with Allen Ginsberg and Fernanda Pivano.

"Miljö för en ny planet" (Landscape for a new planet)

Grand Altare, 1969, Altar. Red ceramic, height: 50 cm, diametre: 250 cm, unique piece © Adagp, Paris 2021 © Centre Pompidou, MNAM-CCI/Service de la documentation photographique du MNAM/Dist. RMN-GP

In response to the invitation of Pontus Hulten, director of the National Museum, Stockholm, Ettore Sottsass made a group of monumental ceramics on the occasion of his solo exhibition, "Miljö för en ny planet" (February 1969). Inspired by India, these ceramics (Altare, Pilastro, Tempio Azzurro) were presented alongside altars and a large neon mandala, as "exercises in concentration".

He wrote: "I made mountains of terracotta, impossible to make, impossible to transport, assemble or use". These works from the Centre Pompidou collection are brought together for the first time: consisting of coloured – red or blue – disks stacked on top of each other, these ceramics resemble tumuli, shamanic totems or primitive architectures. They are presented alongside a large scale Superbox, in a contrast between organic and geometric forms.

In the catalogue for the Stockholm exhibition, Ettore Sottsass evoked the possibility of everyone creating their own "most unexpected and most fantastical" environment. These works should function both on a physical and a psychic register. Their ritual dimension – "altars for the sacrifice of (one's) solitude – is reminiscent of the "caves and deserts of the Middle East", where anchorites and hermits took refuge.

A testimony both to the influence of Pop Art and oriental philosophy in the work of Sottsass, the Stockholm exhibition was contemporaneous with the creation of the Valentine portable typewriter, which would become one of the icons of industrial design, the embodiment of a new modern lifestyle.

New ‘Domestic Landscape’

In 1972, the Museum of Modern Art in New York presented one of the most important exhibitions devoted to Italian design. Curated by Emilio Ambasz, "Italy: the New Domestic Landscape" brought together industrial and radical designers in a contemplation of habitat and the domestic environment.

Ettore Sottsass contributed a new typology of mobile domestic architecture. He elaborated prototypes of identical fibreglass cases on castors, each dedicated to a specific function (shower, toilet, kitchen, etc.).

This container furniture or "micro-environments" respected a principle of modularity and could be combined in a variety of ways, constantly reconfiguring the interior. Neutralising all expressiveness, their material and grey colour resonated with the Mobili grigi series. This furniture was designed as a proposition between "counter-design" and prototypes for industrialisation.

The series of drawings entitled Il Pianeta come festival (1972) acknowledges the impossibility of making architecture as a "model of society".

These drawings by Tiger Tateishi communicate in an ironic manner an architectural utopia in which society, freed from work, has turned to a civilisation of leisure amidst the ruins of modernism.

The nomadic life: photographing the world

Throughout his life, Sottsass never ceased to travel and to take photographs. In Montenegro during the Second World War, he used a Leica to photograph the houses of peasants, mosques, cemeteries, and his brothers in arms.

Photography testifies to his interest in a culture of the anonymous, the "poor". He derived his inspiration from folk culture, vernacular architecture and ancient civilisations. He compared his life to that of a nomad, who travels to survive in the borderline zones between life and death. "I felt a profound necessity to visit deserted places, mountains, to establish a physical relationship with the cosmos."

As if to retain the multitude of his photographs in memory, Sottsass established typed lists on the principal subjects that interested him: ruins, walls, cemeteries, architecture, children, and more. Wishing to leave a lasting trace of this work, he classified his photographs on contact sheets by year and by place, in a dedicated Olivetti furniture unit, now preserved in the Kandinsky Library.

For Sottsass, the Design Metaphors (1971-1978) series of 43 photos was a spiritual exercise in reconquering "the most elementary actions", the quest for "primordial forms of living". Pieces of string, bits of wood, leaves and stones are poor and ancestral materials out of which Sottsass made precarious constructions in the landscape before photographing them, adopting the posture of a conceptual artist or a land artist.

In this photographic work, Sottsass elaborated precarious "constructions" in the heart of mountain landscapes, like unfinished architectures. Design "as a metaphor for life" led him to abandon objects in order to sketch the simple lines of a path or collect poor materials that were destined to disappear. Sottsass gave a title and a subject to each photo, after the fashion of a child's questions. "When I draw a door, for example, to enter the shade, I wish to say that the most important thing is not the drawing of the door, but what lies behind it.".

On the road to Memphis

In 1973, Ettore Sottsass cofounded Global Tools, a "counter-school" of architecture and design, the comet's tail of radical architecture, whose workshops stressed the importance of collective creation, of the body as a prosthetic instrument of design. Sottsass was also one of the founders of the Studio Alchimia in 1976 and in 1981, he founded the Memphis group in Milan. In 1982, he created the Sottsass studio, returning to architecture at 65.

Memphis emerged one evening in December 1980 as he listened to Bob Dylan's song "Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again". Sottsass gathered architects and designers from different generations around him, among them Aldo Cibic, Matteo Thun, Marco Zanini (from the Sottsass Associati studio), Michele De Lucchi, Martine Bedin, Nathalie Du Pasquier, Shiro Kuramata and George Sowden. Memphis may have been more a gathering of creative individualities around Ettore Sottsass and Barbara Radice than a collective, strictly speaking. Barbara Radice was artistic director for the movement.

Memphis promoted another relationship with industry, rehabilitating the designer an opinion leader and revolutionised design with Pop Art pieces with asymmetrical forms, vivid colours and materials such as laminates. This iconoclastic language combined with a form of ambivalence with regard to the functional identity of objects. With its liberating approach to design, breaking away from the functionalist doxa, Memphis deployed a new form of narrativity beyond the notion of style. Highlighting the failures of modern ideologies in favour of an emotional and sensorial dimension of objects, Memphis laid the foundations for a new approach to design. As Barbara Radice suggested, Memphis was part of a new era of connectivity and communication that radically transformed the concept of the object, thereafter increasingly permeated by a dematerialised environment.

This exhibition stresses the decorative renewal introduced by Memphis. In the late 1970s, Sottsass designed several motifs (Bacterio, Serpente, Rete, Spugnato) that created a non-directional pictorial surface. These motifs are like an archaeology of his visual culture, between personal reminiscences and historical references.

The Abet Laminati company supported Sottsass over several decades in the implementation of this research, where the decorative surface fused with the material of the laminate. These decorative motifs would be one of the principal constitutional elements of the objects and textiles created by Memphis.

For Sottsass, "Design is a way of looking at life", "of edifying a possible figurative utopia or a metaphor for life".

In the course of this presentation, from the first years of creation to Memphis, the exhibition showcases the "magical thinking" that runs through the multiplicity of artistic modes of expression that Sottsass used, abolishing the difference between ceramics, furniture, architecture, photography and poetry. For him, all "objects" were the ritual punctuation of a cosmic whole, relating to their "magical" appropriation by man.

The exhibition, curated by Marie-Ange Brayer and Céline Saraiva, runs until January 3rd, 2022.